Does a higher-carb diet contribute (or even cause) diabetes? A recent longitudinal study showed that higher blood sugar just might, adding to the evidence that questions why non-athletes should eat so many carbs. Can intermittent fasting help prevent it?

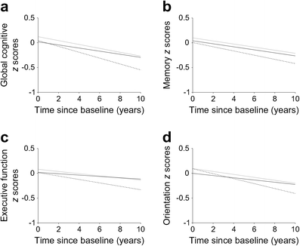

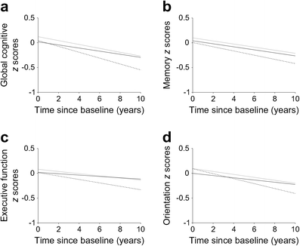

In a recent investigation, a positive correlation was found between high blood sugar levels and cognitive decline associated with Alzheimer’s disorder. This finding is even more terrifying as the correlation is positive regardless of the participant’s diabetic state. In other words: more blood sugar, a faster cognitive decline.[1]

The study is titled "HbA1c, diabetes and cognitive decline: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing", was led by scientists at the School of Public Health at Imperial College London and Peking University Clinical Research institute, and was published in the diabetes journal Diabetologia.

Researcher Dr. Wuxiang Xie stated, "Our study provides evidence to support the association of diabetes with subsequent cognitive decline. Moreover, our findings show a linear correlation between circulating HbA1c levels and cognitive decline, regardless of diabetic status."[2]

How the new analysis worked: Longitudinal Data

First, we need to establish how this conclusion can be reached. This new investigation relied on data pulled from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA),[3] specifically the "waves" of data collected from 2004 to 2015. This is effectively a huge sample set of health data on the aging English population (aged 50 and older), and it's broken up into seven two-year waves spanning a total of 14 years. The study we're about to discuss used waves 3-7.

A longitudinal analysis is any study that measures a certain variable or set of variables over time. For example, analyzing the pathogenesis of an illness like Parkinson’s in similar patients over twenty years would be considered a longitudinal study.

By relying on the waves of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing from 2004 all the way to 2015, the researchers had 11 years of data to examine - and trends can be spotted. They were able to analyze over 5000 participants, which is more than enough to achieve statistical significance even in a large population.

During each ‘wave’ or repetition of the study, participants underwent a cognitive battery and had their HbA1c levels measured via a blood test. HbA1c, or glycated hemoglobin measurements, allows for a simple way of tracking blood-glucose levels over the course of time, and is one of the most important numbers to analyze for overall metabolic health and well being.

Upon analyzing the collected data using statistical tools, researchers realized that participants performed worse on the cognitive test as their HbA1c levels increased. In research, this is referred to as a "negative correlation".[1]

Dr. Wuxiang Xie also commented to news.com.au,

"Our findings suggest that interventions that delay diabetes onset, as well as management strategies for blood sugar control, might help alleviate the progression of subsequent cognitive decline over the long-term."[2]

With that in mind, and trusting that this dataset is large enough to be of significance, we need to look at our latest understanding of Alzheimer's Disease and see if there are any underlying metabolic mechanisms that need further research and understanding. It turns out there are.

Getting Started: What IS Alzheimer’s Disease?

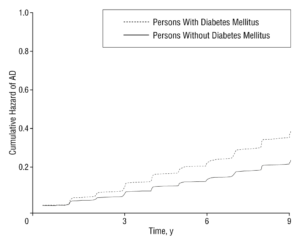

The long story short from the study is that the dotted lines are the participants after diagnosis of diabetes. Their cognition levels decline well below the rest.[1]

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is defined as a chronic neurodegenerative disease that worsens as the disease progresses. AD is also thought to cause about 70% of all dementia cases seen in clinics around the world. The disease breaks down the essence of what makes us human. For example, one may lose their ability to communicate, their ability to tell where they are in the world, or even have their behavior or attitude shift for the worse.[4,5]

As Alzheimer’s progresses, the patient will see their bodily functions fail until death occurs. It goes without saying that this disease is beyond tragic and immensely painful for everyone involved, from the patient to their family, friends, and loved ones, to the doctors themselves.

As if the disease weren't frustrating enough, the cause is still generally misunderstood even to researchers. Decades of research have often resulted in an abundance of dead ends, with each promising lead resulting in little progress in actual disease management or treatment. As of now, our best guess is that the disease is related to amyloid plaque and protein aggregate formation within different parts of the brain.[6]

Blood Sugar and Alzheimer’s Disease: The Enzyme Theory

More recently, Alzheimer’s Disease has been called a “third” diabetes,[7] or "Type 3 Diabetes". While this term originally sounded like a stretch, it makes sense when considering that people with diabetes are at a much higher risk of developing AD.[8] The higher risk of AD is true for people suffering from both types of diabetes.

Due to this theory, some newer studies are investigating attacking Alzheimer's by directing immunotherapy at Amyloid-ß.[13]

But while Diabetes Type 1 and Type 2 are very different illnesses, they share a common factor. Why is it that both diseases share a heightened risk of cognitive decline? It may come down to enzymes.

A particular enzyme, named insulin-degrading enzyme (you don't need a degree to figure out what this one does!) has been studied in AD research for years. Besides breaking down insulin, it also breaks down amyloid plaque. The enzyme is also derived from insulin in the first place![9,10]

Breaking down amyloid plaque: the secondary function of insulin-degrading enzyme

With this understanding, the heightened risk of AD for those with diabetes makes more sense: there is a secondary function for insulin-degrading enzyme (breaking down amyloid plaque), but it never gets accomplished if insulin is too busy breaking down blood sugar!

Another meta-analysis conducted determined nearly the same thing: greater blood sugar, more Alzheimer's Disease risk.

Those with Diabetes I never naturally produce enough insulin to have adequate levels of insulin-degrading enzyme to break down amyloid plaques at an appreciable rate. Those with Diabetes II will have enough insulin in their blood that insulin-degrading enzyme will spend most of its time degrading plasma insulin instead of focusing on plaque buildup.[11]

So either way, if blood sugar remains too high, insulin-degrading enzyme may not get to its secondary function because it's constantly dealing with the insulin itself, which may eventually take an insanely serious toll on the brain.

This theory is promising. The co-writer of this article has a degree in neuroscience, and even we were stricken by this idea, as we'd never considered the possibility. Researchers at the Mayo Clinic even agree with this hypothesis. Protip: If Mayo Clinic researchers like something, there's a good chance it’s legit.

I Don't Have AD -- Why Should I Care?

If you were paying attention well in the last section, this has already been addressed - it's all about the enzyme. Insulin-degrading enzyme can get caught up in breaking down insulin floating around the body. When you eat carbohydrate heavy meals, your body releases insulin. Insulin is an anabolic hormone designed to store resources for later use.

If we’re forcing out insulin-degrading enzymes to work on our insulin spikes related to diet, we do not allow the enzyme to perform the secondary function of amyloid plaque degradation.[8]

In layman's terms, the metabolic system needs time to flush things out, but it cannot do so if you're packing yourself full of carbohydrates non-stop.

Low-carb diets (and the keto diet) may help

The reasonable solution? A lower-carb diet, possibly (but not necessarily) even a ketogenic or carnivore diet! Moderating carbohydrate intake, even in non-diabetic populations, has been shown to reduce your chances of developing dementia.[9] If the insulin-degrading enzyme is to be believed, we have an obvious solution.

In the case of the keto diet, if your body is only producing ketones, your insulin-degrading enzymes will be given the proper time to destroy amyloid plaques that may form in different parts of your body.

Consider a longer fasting period (such as daily intermittent fasting)

Still other studies show it plainly: more carbs, more MCI (mild cognitive decline). So why are we getting so many carbs thrown at us every day?

Intermittent fasting may also give your body a chance to "catch up" as well, as alluded to above. It's possible that you don't necessarily need to remain completely ketotic, but could just go through moderate fasting periods to give insulin-degrading enzyme time to do something aside from working on insulin itself. While this part is theoretical, there are definitely several other benefits to fasting (lower blood pressure, weight loss, serum triglyceride improvement),[12] which could happen in parallel here.

Many users report that 14 or 16 hour daily fasts are when they start noticing good changes. This means you'd have 10 (or 8) hours to eat, which is often enough to get enough calories in. (Example: Only eat between 11am and 7pm). The other hours help reduce blood sugar and give the body a chance to perform secondary functions not related to eating/digestion, aiding in some of the cardiovascular and weight loss benefits cited above.

Expect to see more research on fasting and cognition

With all of ongoing research with the keto diet and intermittent fasting / time-restricted eating, we believe that we'll see a lot more coming out in this regard, but unfortunately we don't know for certain how useful these diets can be, especially when started later in life. For anyone out there who is willing to do anything it takes, it's definitely worth bringing this research up to your doctor and discussing a low-carbohydrate, time-restricted dietary intervention - but only under the care of your physician and a dietician.

Conclusion: Another ding against carbs and high blood sugar

If this hypothesis is correct, the entire country might have to rethink how we approach diet, especially as we get older. Alzheimer’s Disease is the sixth leading cause of the death in the country! While there are still just a handful of studies supporting this theory, their results are in line with everything else we're learning about high carbohydrate intake damaging the mitochondria and causing other major health problems.

A universal pattern of serious health damage is developing, and it's not difficult to see once you read enough literature.

As always, we recommend that you speak with your physician and get their written approval before making a lifestyle or dietary switch, but for the average non-athlete, we really don't see the purpose of so much blood sugar spiking carbohydrates (or even the over-consumption of protein!)

In a perfect world, the ideal investigation would be a long-term study investigating rates of dementia development in people that stick to a low-carb diet as a type of "control group" compared to those that prefer higher carbohydrate intakes. Alzheimer’s is a multi-faceted disease that is likely not caused by a single factor.

However, attacking the insulin angle -- and that means carbohydrate (and to a lesser degree, protein) consumption -- might be the first step towards understanding better treatment. So tell us... why are we eating all those carbs again?

References

- Zheng, F., Yan, L., Yang, Z., Zhong, B., & Xie, W; Diabetologia; "HbA1c, diabetes and cognitive decline: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing"; January 25, 2018; https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00125-017-4541-7

- Togoh, I; "Diabetes link to cognitive decline: study"; News.com.au; January 25, 2018; http://www.news.com.au/world/breaking-news/diabetes-link-to-cognitive-decline-study/news-story/ecaacd8cfb628dea9693a8c002a93184

- ELSA: English Longitudinal Study of Ageing; The Institute for Fiscal Studies; http://www.elsa-project.ac.uk/

- World Health Organization; "Dementia Fact sheet"; March 2015; Archived from the original on 18 March 2015; https://web.archive.org/web/20150318030901/http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs362/en

- Burns A, Iliffe S; "Alzheimer's disease"; The BMJ; 338: B158; February 5, 2009; http://www.bmj.com/content/338/bmj.b158

- Rubenstein, R; "Amyloid Protein Precursor in Development, Aging and Alzheimerʼs Disease"; Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders; 11(3), 179; 1997; https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-662-01135-5

- De la Monte, S., & Wands, J; "Alzheimer's Disease Is Type 3 Diabetes–Evidence Reviewed"; J Diabetes Sci Technol; 2008; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2769828/

- Arvanitakis, Z., Wilson, R. S., Bienias, J. L., Evans, D. A., & Bennett, D. A.; "Diabetes Mellitus and Risk of Alzheimer Disease and Decline in Cognitive Function"; Archives of Neurology, 61(5), 661; 2004; https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaneurology/fullarticle/785863

- Pivovarova, O. et al; "Insulin-degrading enzyme: new therapeutic target for diabetes and Alzheimer's disease"; Ann Med; 2016; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27320287

- Schilling, M. A; "Unraveling Alzheimer's: Making Sense of the Relationship between Diabetes and Alzheimer's Disease"; January 1, 2016; https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-alzheimers-disease/jad150980

- Roberts, R., & Roberts, L, et al; "Relative intake of macronutrients impacts risk of mild cognitive impairment or dementia"; J Alzheimers Dis; 2012; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3494735/

- Palgi, A et al; “Multidisciplinary Treatment of Obesity with a Protein-Sparing Modified Fast: Results in 668 Outpatients”; American Journal of Public Health; 75.10, 1985: 1190–1194; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1646394/pdf/amjph00286-0076.pdf

- Lannfelt, L, N R Relkin, and E R Siemers; “Amyloid-SS-Directed Immunotherapy for Alzheime’rs Diseas”; Journal of Internal Medicine 275.3 (2014): 284–295; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4238820/